Headwinds to German public investment should temper some of the near term euro bullishness – even as it leaves the longer term case intact.

Photo by XS Xue on Unsplash

Executive summary

There is a substantial and so far underappreciated risk of public investment underperformance in Germany. The government’s intention is for its infrastructure spending package to be frontloaded, but the current dire state of local government finances means it faces an uphill struggle.

While 100bn euro of new money earmarked for federal states and local councils are likely to help, there are also significant structural obstacles at local government level that could delay implementation. These include lack of planning staff at local authorities, shortage of (construction) workers, complicated planning regulations, and lengthy consultation and approval periods for projects.

Whether the new government’s planned legislation to remove some of those obstacles will prove effective at speeding up projects remains to be seen.

Macro implications. My assumption on the German package has been from the beginning that – as far as its impact on the economy is concerned – it’s a story for 2026 and beyond. For now, on the whole I see risks tilted towards later spending and implementation. That should temper some of the bullishness on the euro in the near term – while I still think the long term case for a stronger euro remains intact.

Germany created quite a ruckus in markets when the incoming government decided to increase spending on infrastructure and defense by a whopping 500 bn euro or 12% of 2024 GDP.

This investment is at the heart of many a bullish case on Europe – including my own.

Now, Germany has a public investment blockage which has been a cause of concern for some time already.

A major question then is when – even whether – Germany will be able to spend the overdraft that the government has granted itself.

So, in this post I will look at German public investment in all the gory detail – I’m afraid this will be a long, nerdy post.

Back to the basics

Let’s start with some basic numbers.

German total gross public investment in 2024 (2023) was 126bn (118 bn), or 2.9% of GDP (2.8% of GDP).

That compares unfavorably to its peers - see the comparison below from the International Monetary Fund.

source: IMF, p.4

Note also that net public investment – what is left over after accounting for depreciation on existing capital, in short, the net addition to the public capital stock – is much lower, indeed puny: in 2023 (latest available data on net public investment) it was 3.3bn, or 0.08% of GDP!

Germany has been barely able to maintain its public capital stock constant over the last three decades.

I’ll come back to this in a minute.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

The structure of gross public investment

Let’s have a look at what the money is spent on and by what level of government.

The latter is important as Germany is a federal republic, and its constitution assigns different tasks to the various levels of government.

Not surprisingly, most of the money – about 60% in 2024 - is spent on construction projects, i.e. infrastructure investment. Gross investment in machinery and equipment, and other investment (software etc.) make up the remainder roughly equally. While the construction share was getting squeezed somewhat over time, over the last five years or so it has recovered slightly.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

When it comes to infrastructure investment in particular, the split between the various levels of government is important.

Gross investment in construction is mostly done by local authorities.

They build bridges, schools and administrative buildings and account for half of every euro spent in Germany on infrastructure. The federal government comes second with 30%, followed by the federal states with about 20%.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

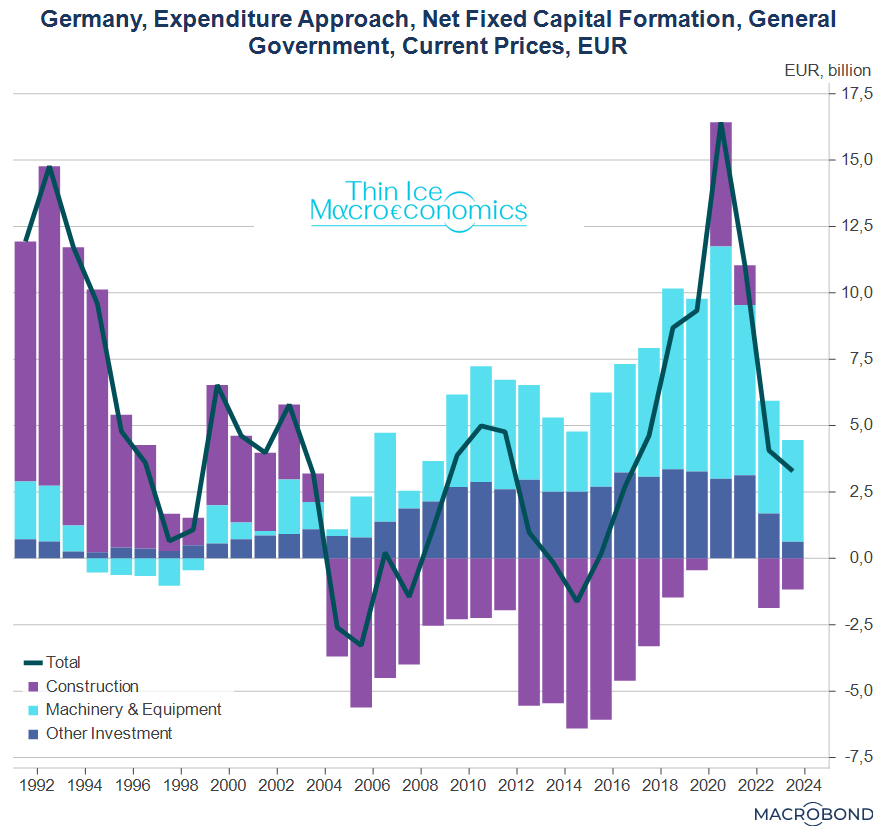

Now let’s go back to net investment (remember, net investment equals gross investment minus depreciation).

Here’s the breakdown of net public investment between infrastructure (construction) and the remaining types.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

What pulls down the net investment numbers for a good twenty years now is precisely the construction category (purple bars).

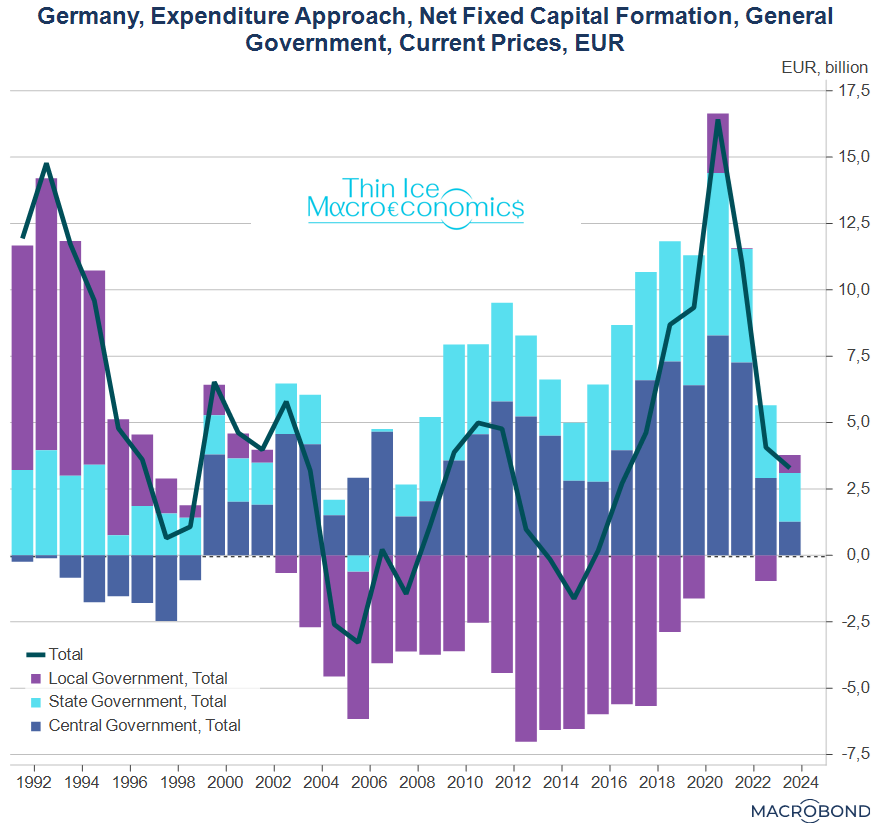

And here’s how net investment breaks down across the three layers of government – central government (that’s the federal – or Bund – level), the federal states, and local government.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

What’s striking is that net investment by local government is almost unfailingly negative since the turn of the millennium. In 2023 (latest available data), local authorities managed a rare positive net investment (0.7bn of the total 3.2bn of net public investment).

In fact, prior to 2023 local authorities hadn’t managed positive net investment in construction since 2002 (following a public construction investment boom in the 1990s due to German reunification).

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

So, we have zeroed in on a major culprit of german public investment underperformance.

Infrastructure investment accounts for 60% of overall gross public investment. Half of gross investment in infrastructure is carried out by local authorities, and they are struggling to achieve positive net investment, i.e. to simply maintain the stock of municipal infrastructure.

Boom and bust

The reason is simple: the state of local government finances.

In Germany, local governments are responsible for a great deal of the social safety net like providing housing, paying benefits etc. Such spending is difficult to avoid or even to control as it may depend on extraneous circumstances such as

the state of the national economy

national policies over which local councils have little control (such as the level of benefits).

As a result, local authorities have very rigid expenditure.

What’s more, many are highly indebted, which forces them to spend a substantial amount on interest.

On the other side of the ledger, local authorities’ income is very volatile.

They levy some local taxes such as council tax on households and trade tax on local businesses, with the latter being highly variable over the business cycle. They also receive some fixed share of tax intake that otherwise accrues to the federal and/or state government (such as income tax and VAT).

As the federal constitution stipulates “equivalent living conditions” across the country and the revenue-raising ability of local authorities’ varies widely, there’s also an elaborate system of grants from the federal and state governments towards local authorities, as well as a complicated system of redistribution from stronger local councils to weaker ones.

Overall, this structure of revenue and outlays makes local authorities’ budget balance highly variable.

As the chart below shows (with the budget balance shown in % of expenditure), this leads to a pronounced cycle of boom and bust in local government infrastructure investment.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

Investment bust ahead?

Last year, local councils in aggregate ran a deficit of 24.8bn euro, or 6.2% of expenditure (a record for both).

The chart suggests that this doesn’t bode well for this year’s local government infrastructure investment spending (note the deficit series is shifted to the right by one year).

In fact, according to a KfW survey (in German), sentiment among city treasurers about the state of local government finances this year is pessimistic, with 84% of them rating their authority’s situation as “disadvantageous” or “very disadvantageous”. These responses sum to 91% for the next five years.

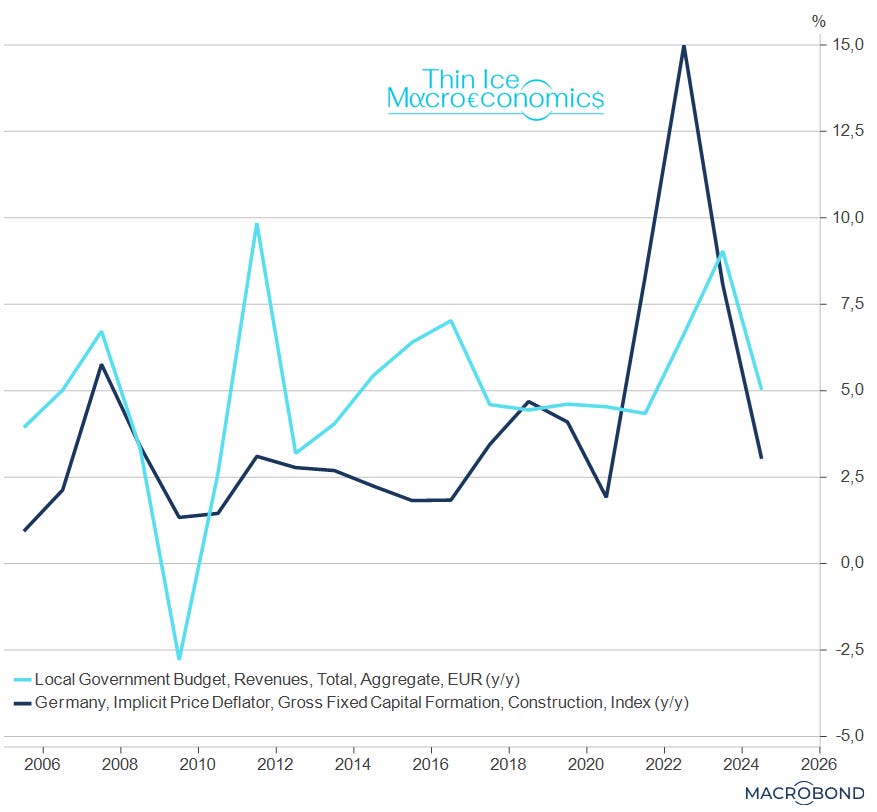

A key challenge is that revenue growth is hit by economic stagnation, while costs soar – during 2021-23, construction cost inflation by far outpaced local authorities’ revenue growth.

Source: German Federal Statistical Office, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

Estimates for local authorities’ tax intake (link in German) over the coming five years have been revised down recently.

The system needs broader reform

This is the backdrop for the federal government’s infrastructure splurge.

It is certainly good news that 100bn euro of the package’s 500bn euro have been earmarked jointly for the federal states and the local authorities. The latter are asking for at least two thirds (link in German).

According to the KfW paper, the money should help deal with the investment backlog at local level.

However, it does not deal with many local authorities’ structural problems.

These can only be addressed through a reform that structurally improves councils’ finances, for example by increasing their share in federal income tax and VAT receipts. On the expenditure side, local government shouldn’t have to foot the bill for decisions made elsewhere, especially at the federal level.

In short, councils should be given more power over their budget.

More headwinds

Other headwinds to infrastructure investment for local authorities are not new.

They include (link in German) lack of planning staff at local authorities, worker scarcity in the construction sector, and complicated planning regulations, including lengthy consultation periods for new projects.

Last but not least, the high degree of variability of income sources – especially the trade tax – reduce long term visibility and stunts incentives for councils to hire more planning staff.

Recognizing some of these issues, the new government’s coalition agreement includes a number of legislative initiatives intended to speed up planning, permitting, procurement, and tendering for infrastructure projects.

The acceleration works by assigning such projects “superior public interest” status, which would also cut through stringent environmental regulations.

Such treatment is said to have significantly sped up some government projects recently.

Macro implications

Whether this can actually work at the much larger scale now required remains to be seen. Until then, I would view risks to spending and implementation – which I always thought was a 2026 and beyond story – as being tilted towards later.

Infrastructure spending is today’s demand and – as it enhances the economy’s capital stock – tomorrow’s supply.

State of the art macro models assign large values to government investment multipliers.

So, it goes without saying that the government’s ability to bring infrastructure projects to fruition quickly is important for Germany’s macro outlook. For example, as a result of the infrastructure package, the European Commission sees GDP being 1.25% higher by the end of the current legislature (2029).

For now, I think the headwinds to investment I described should temper some of the near term euro bullishness – even as it leaves the longer term case intact.

This article highlights significant risks to Germany’s public investment, especially at the local government level, where funding issues, labor shortages, and red tape delay infrastructure projects. Despite the massive 500 billion euro spending plan, these bottlenecks could slow implementation and temper near-term euro strength. Structural reforms to give local councils more financial control seem essential.

Given these challenges, will Germany be able to deliver on its infrastructure promises soon enough to support sustained economic growth?

Where is the fiscal multiplier stronger, under federal or local spending? Or is there a distinction