source: British Library via Unsplash

Bulgaria’s impending adoption of the euro, making it the 21st country to join the single currency, got little attention in markets.

After all, adding what is a relatively small economy to the euro area looks like a non-event – especially when seen against the backdrop of escalating geopolitical tensions as per what now looks like a fully-fledged war between Israel and Iran.

Background. Following favourable reports from the European Commission and the European Central Bank, Bulgaria is seen to have fulfilled accession criteria for joining the common currency on January 1st, 2026.

Yet there is a geopolitical dimension to Bulgaria’s euro accession, which I want to tease out here (we’re all geopolitical analysts now).

First though, the bigger picture.

Geopolitics and the euro

The euro is in close proximity to the two major wars happening right now: the Middle East, and of course Ukraine.

What’s the market verdict on the euro and geopolitics?

It’s a bit of an axiom in markets that the euro doesn’t metabolize geopolitical risk well – conversely, that the dollar strengthens when there are geopolitical ructions due to its safe haven status.

Looking at the EURUSD cross vs an index of geopolitical risk (I’m showing the price of dollars in terms of euro, which goes up when the risk index rises) shows this is mostly a very short run phenomenon.

source: Matteo Iacovello, Macrobond

Which makes sense, given that

geopolitical events themselves tend to be mostly short-lived (famous last words!)

they are not existential for either the US nor the euro area, and hence

other – mostly economic – forces prevail most of the time.

The obvious exception to all this is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It seems to have triggered a quasi-permanent upshift in geopolitical risk (an increase in the level of the blue line in the chart), and it seems to have ushered in a weaker regime for the euro (an increase in the price of dollars, in euros – the light blue line).

Which is hardly surprising: the resulting energy price shock weakened (parts of) European industry for good, imparted a major income shock on households, and forced the ECB to raise rates to higher levels than it probably would have – and to keep them there for longer.

Bulgaria and the euro

Now, what does Bulgaria’s accession mean for the geopolitical dimension of the euro?

Geography and history. Bulgaria’s euro accession extends the writ of the common currency further into central and eastern Europe – countries that used to be part of the “Soviet bloc”. One way of looking at this is that it underscores the important historical mission of the European Union, namely to heal the cold-war division of Europe.

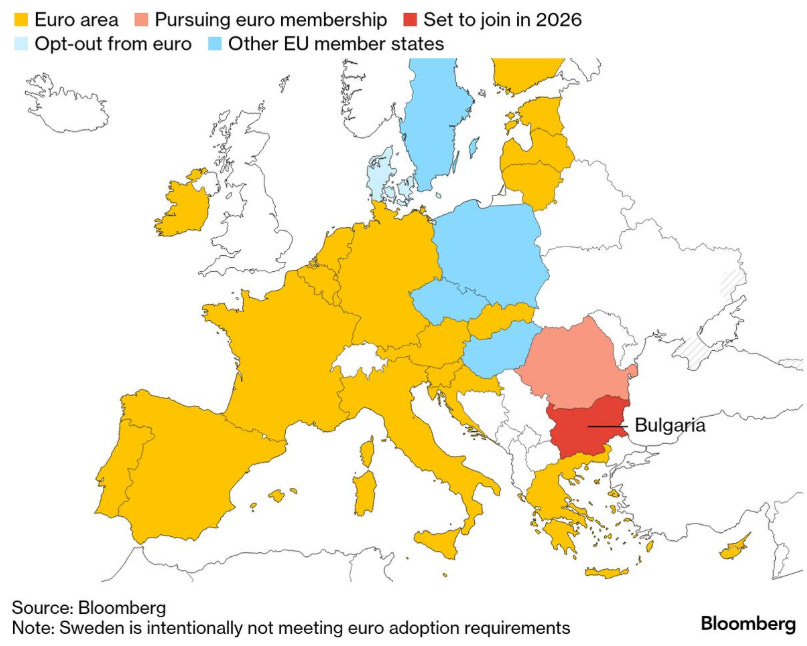

Bulgaria therefore joins a set of countries that were behind the “Iron Curtain” and are now members of the single currency, namely Slovenia, Slovakia, and the three Baltic republics: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Which also means that, geographically, the euro is far from the Western European project that it’s widely perceived to be.

Bulgaria joining the euro also expands the geographical reach of the single currency all the way to the Black Sea – a flashpoint of the antagonism between Putin’s Russia and “the West” (or the EU).

source: Bloomberg

(Of course, four euro area countries have a direct border with Russia: Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (the last two also share a border with close Russian ally Belarus).)

Culture and politics. After Greece, which joined the euro in 2001 (two years after the euro was adopted but in time for the rollout of notes and coins), and Croatia, which joined in 2023, Bulgaria is the third country from the Balkans – the South Eastern European peninsula – to adopt the common currency.

Croatia can probably be called Western European by culture and religion – it’s Catholic – as well as history – it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg empire until it became part of the kingdom of Yugoslavia following the end of the First World War in 1918.

Greece on the other hand is Christian Orthodox. But she has, for all intents and purposes, always been politically part of the Western alliance: a long-standing member of NATO (it joined the alliance, which was founded in 1949, in 1952) and the EU (which it joined in 1981).

Bulgaria has in common with Greece that it is predominantly Christian Orthodox (with a sizable Muslim minority of about 10% of the population).

Western media report extensively on the opposition of pro-Russian political forces in the country to the euro.

But this is by no means exclusive to Bulgaria, even if some of this is likely cultural (besides also being Christian Orthodox, the Bulgarian language is one of the closest to Russian in the Slavic group of languages).

Yet even the “hard core” of the euro area has to contend with pro-Russian populist forces, e.g. the Alternative for Germany or the Rassemblement National in France.

Geopolitics, the Euro, and Bulgaria

Thus, euro adoption also ties Bulgaria more firmly into the Western camp.

For one, it means deeper participation in European institutions, most obviously by having the Bulgarian central bank become part of the European System of Central Banks and the country having a say in ECB monetary policy (which is not the case under the current arrangement – a currency board pegging Bulgaria’s currency, the lev, to the euro).

Ultimately, it’s one thing to be in the EU (since 2007) and NATO (since 2004), quite another to share the euro: it gives citizens – whatever their current misgivings - something tangible.

Indeed, according to Scope Ratings, deepening and broadening the EU and the euro while Russia continues its war against Ukraine may have been part of the accession calculus.

What does all this mean for the price of the euro going forward – how its exchange rate responds to geopolitical shocks?

(See here for my general verdict on the euro as a dominant currency.)

That the euro weakens in response to geopolitical shocks probably won’t change – at least until Europeans are willing and able to use and project hard power, at least in their immediate neighborhood.

Which – at best – is work in progress.

(Incidentally,

argues that this is because of the requirement for unanimity in EU foreign policy. I’d argue that even in the case there was unanimity, being prepared to, for example, deploy troops on a large scale in Ukraine, would be too much for most European electorates to stomach. That is, the real constraint ultimately is how far Europeans themselves are prepared to go.)And specifically on Bulgaria’s accession, the country’s geographical position on the Black Sea as well as its internal divisions, with strong pro-Russian political forces, probably means that the euro would, on the margin, become more susceptible to geopolitical risk.

But again, the impact on the euro of pro-Russian political forces gaining more traction in either Germany or France would probably be even greater.