ECB: Worker Bargaining Strength to Limit Cuts

Labor gets a larger share of the pie

Labor is likely to remain scarce in the euro area. The tightness of the labor market strengthens workers’ bargaining position, helping them secure a larger slice of the pie: the share of wages in GDP will remain elevated. This is likely to limit the space for ECB cuts: workers’ bargaining strength is relevant for the terminal rate.

The trajectory of wages in the euro area remains key for the ECB rates outlook.

To quote President Lagarde in Sintra: “ .. what’s behind it is a lot of wages. Services has a very high component of labor. Wages also suffer from the lag impact of the labor system.”

Labor scarcity persists

What drives wages? The obvious place to look for an answer is the labor market.

Companies are struggling to fill job vacancies - labor is scarce. That’s what euro area businesses’ reporting of labor availability as a factor that limits production suggests (chart below).1 This indicator remains well above pre-pandemic levels (with some difference between services and industry).

Firms are saying: the labor market is tight.

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond

Firms’ assessment of how much difficulty they’re having to find workers provides a more timely measure of labor scarcity or labor market tightness in the euro area than job vacancies data, which is published with a longer delay; and is a better indicator than the unemployment rate, which exhibits little variation of late (chart below).2

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond

Thinking about tightness

To understand whether the labor market will remain tight going forward, we need to ask what drives the tightness.

One answer could be demand for companies’ products. If demand is strong, firms will look to hire workers, and vice versa.

As it happens, the same business survey also asks companies whether demand for their output is a factor that limits production.

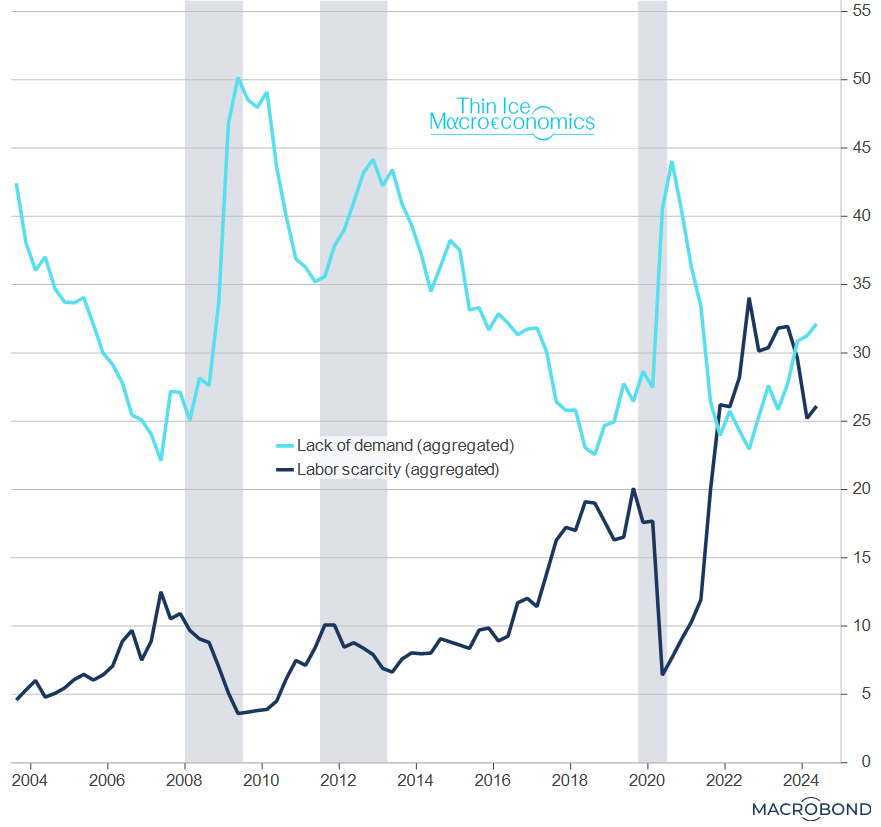

The chart below contrasts the extent to which companies see the two factors, labor and demand, as a constraint (for each factor I have aggregated industry and services into a single series, called “labor scarcity” and “lack of demand”, respectively).3 The grey shadings are recessions.4

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

The importance of the factors varies with the economic cycle, especially for the demand factor.

That, of course, is as it should be.

From a company’s point of view, recessions are characterized by a lack of demand. As a result, companies cut down on their hiring. Further, recessions boost unemployment, increasing the number of workers looking for jobs.

From both the demand side and the supply side then, tightness of the labor market decreases when the economy is weak, and companies perceive less worker scarcity: the dark line in the chart above goes down in a recession.

Covid put the labor market in a tight spot

Recently, “demand” became an increasing constraint for companies (the turquoise lack-of-demand line climbs from 22Q3 onwards as the economy weakens due to the energy shock following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and the ECB’s rate hikes).

This made the labor market somewhat less tight - labor scarcity eased as lack of demand reduced firms’ need for workers. But not much.

Labor scarcity has now bottomed at a much higher level than before the pandemic. The euro area labor market has remained tight despite several quarters of sluggish, even negative, GDP growth.

And as of the second quarter of this year, labor scarcity is increasing again - and we have seen (first chart above) that this is due to the services sector.

The recovery that has started should make the labor market even tighter.5

Why did covid increase tightness of the European labor market?

This deserves a separate post, and I’ll readily admit that I don’t have a full answer.

From the labor supply side, people seem to want to work fewer hours (perhaps helped by a lower risk of unemployment due to furlough schemes); or are only able to work fewer hours (due to long covid, and we have also seen an increase in “regular” sick leave). On the demand side, the demographic transition may be inducing firms to hoard labor.

Labor’s share of the pie increases

What are the consequences of a tighter labor market?

The increase in labor scarcity is marking a shift in bargaining power towards workers (and away from employers). When the labor market becomes tighter, filling vacancies becomes more difficult for firms. That strengthens workers’ position when bargaining for wages.

Put differently, the labor scarcity variable is a proxy for workers’ bargaining strength.

Now, common sense as well as economic theory – yes, they do coincide occasionally! – suggest workers should be able to increase their share of the “pie”. In macro-speak: the labor share of income should rise.6

What does the data say?

There is evidence in the euro area that a tighter labor market boosts the wage share of income (see chart below).7 In particular, higher worker bargaining strength results in a higher wage share with a lag of eight quarters.

Why eight quarters – and not three, seven, or twelve? Because 2 years is the average duration of wage contracts in the euro area (President Lagarde’s “lag impact of the labor system”).

Source: Eurostat, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

The historical relationship therefore suggests that the wage share is likely to remain elevated over the next two years.

A floor for ECB policy rates

What does this mean for inflation and the ECB?

Both wages and profits have been driving inflation in recent quarters. Profit growth has eased substantially lately, allowing inflation to decline amid still very sturdy wage growth.

But workers’ bargaining strength implies that they will continue trying to claw back purchasing power losses suffered in recent years - and may be succeeding.

As a result, the ECB will have to suppress demand sufficiently to keep profits in check if it is to achieve its inflation target sustainably. This will limit the number of interest rate cuts that are ultimately possible.

Put differently: labor scarcity and workers’ bargaining strength are relevant for the terminal rate.

This data is a diffusion index from the European Commission business survey. The question about factors that limit production is asked quarterly – the next release should be out at the end of July for the third quarter of 2024.

For the same reasons, it is more useful in real time than the ratio of vacancies to unemployment (“V-U ratio”), which in principle would have been my preferred measure of labor market tightness. I have aggregated industry and services into a single “labor scarcity” series by weighting by gross value added. The series look very similar:

Source: Haver, Macrobond, National Statistical Offices, Eurostat, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

Industry and services are aggregated by using their shares in gross value added.

Recession dates are from the Euro Area Business Cycle Network.

Another way of looking at this is to regress the labor scarcity factor on the “lack of demand” factor, i.e. to ask how much the economic cycle - demand - explains labor market tightness. The chart below shows the part that’s not explained by lack of demand (the regression residuals). The unexplained part takes off in the second half of 2021, and doesn’t come back to earth. In other words, something happened with the pandemic that increased labor market tightness, which cannot be explained by demand in the economy.

source: Eurostat, Macrobond, Thin Ice Macroeconomics calculations

“Labour scarcity … will put [workers] in a stronger bargaining position … They will use that position to bargain for higher wages.” Goodhart and Pradhan, The Great Demographic Reversal, p. 69.

I’m using the share of wages and salaries in gross value added (GVA), although the conclusions are the same when using the share of employee compensation in GDP. The spike in the wage share in 2020Q2 results from the collapse of GVA due to pandemic restrictions while employees continued to get paid, in part with government help.

Very interesting analysis Spyros. It confirms my concern that wage pressures will make the ECB's job harder for longer. It also highlights the need for the Eurozone to reform both its labor market and its immigration framework. Start with the fact that the Eurozone suffers labor scarcity at 6 1/2% unemployment rate, compared to the US's 4%.

Much more interesting and paradoxical: the labor scarcity index in your charts shows a first sharp upward move starting around 2015 - or so, just when Europe started experiencing a strong rise in immigration. This is startling, given that we always hear that Europe needs more immigration to boost the labor force in the face of an aging population.

My impression looking at your chart is: immigration helps boost demand (the lack of demand index keeps dropping), but cannot alleviate labor scarcity because institutional constraints make it hard for immigrants to join the labor force. As a consequence, labor scarcity gets paradoxically worse.

Unless Europe makes it easier for immigrants to integrate in the labor market, immigration will remain a political and social headache with little economic benefit. Would be curious to hear your thoughts here.

Very interesting analysis and agree that labor scarcity is creating pressure on wages. but are wages the drivers of inflation? You refer to the ECB bulletin and I would need to read to have a better assessment but I would also consider the possibility that wages are just catching up with inflation.